Indira Gandhi Used the Constitution : When Democratic Tools Became Weapons of Authoritarianism

Addressing Parliament as Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi would engineer most of her constitutional Cheap tramadol buy online manipulations here.

There are not many in the Indian political history whose shadows are as long as that of Indira Gandhi. The lady who famously declared – India is Indira and Indira is India, had proven with sinister accuracy how the wordings of the constitution that was made to safeguard the democracy, could in fact be used against itself. Her story in passing through a reluctant politician and an authoritarian leader who suspended the very institutions of Indian democracy exposes people to a masterclass in constitutional manipulation that would make Machiavelli take down his own notes.

The Builder of own Rise to Heaven

Indira Gandhi as a child with her father Jawaharlal Nehru learning politics and intricacies of Indian constitutional system

Who would have seen after Indira Gandhi became the first lady walking into the Prime Ministers office in 1966 that a constitutional crisis will take place under her leadership. She was the daughter of Jawaharlal Nehru and not only did she proceed to inherit the political legacy but she was exposed to a clear comprehension of the constitutional framework which her father played a great role in formulating. It is this detailed understanding of the system weaknesses than would subsequently be used by her to override democratic conventions in a systematic manner.

Her first years in office were characterized with challenges that were enough to motivate any leader. The economic collapse, violence in society, and internal political opposition within her party amounted to an ideal storm, which should be resolved with resolve. Nevertheless, rather than operating under the confines of the democratic order of things in effort to remove these problems, Gandhi started to perceive the Constitution as not the holy word, that dictated her actions, but as a set of instruments that could be used to fit her political lifeline.

The First Cracks: Reforming Powers of President

The process of subverting the entire constitution called Gandhi was initiated with the subtlety of a well thought reinterpretation of the role of the President of Indian democracy. The President was supposed to be ceremonial and he was supposed to have limited discretionary powers as envisaged in the Constitution, to largely act on the recommendations of the Council of Ministers. Nevertheless, Gandhi knew that gaining the control of the presidential office would grant her unmatched power over the whole political spectrum.

She first significantly altered the constitution by ensuring that only those presidents that would bend to her political beliefs were selected. Gandhi engineered the election of V.V. Giri as President in 1969 when the Dr. Zakir Husain died even though there was opposition amongst her own party. This action proved that she was ready to break party ranks, so that she can lock down constitutional appointments to advance her long term political agenda.

The connotations of this approach became visible when the President started utilizing his office in order to justify the actions that at the limits of the constitutional decency being implemented by Gandhi. Presidential ordinances whose intentions were to act temporarily to be used on urgent matters were normal acts of government which could avoid parliamentary restriction and discussions. It created a precedent of the circumvention of the Constitution that would increase exponentially in the years that followed.

Hoping to Cash in: the Nationalization Bet

The headlines in newspapers about the nationalization of banks in 1969 which avoided the debate in parliament by manipulating the constitution

Probably, the nationalization of banks in 1969 was one of the most accurate examples of the constitutional manipulation by Gandhi. Although the policy, in itself, was economically and socially justified, her way of doing that proved that she was ready to go through the means of using the constitutional points to score political goals without respect to democratic values.

Gandhi was aware that nationalization of banks was going to be a controversial subject with her in her party and in Parliament. Instead of going through democratic debating process, building consensus and then passing it to law, she instead decided to exercise the ordinance making power on behalf of the President to set the policy through the back door by herself. The action had several functions: it has presented her as an advocate of the poor and the marginalized, and at the same time may show how she is capable of tricking around the formally attested power systems.

A legally permissible cloak on this move has been provided by a free interpretation of directive principles of state policy, which asked the state to reduce inequality in wealth distribution. The problem was that Gandhi considered that the nationalization of banks was not only a good idea but also a constitutional duty. This reading took the limits of constitutional interpretation to extremes, turning in effect aspirational to urgent legal requirements.

The political advantages were at hand and immense. The nationalisation of the banks had a great appeal to the masses who felt it was an attack on direct attack on the economic elite. More perilous, however, was the constitutional precedent which it created. Gandhi had established that decisions of complex policy could be executed by a whims of the executive, which were covered with a cloak of constitutional legitimacy, without involving the permission of the parliament or the necessity of a public discussion.

The Confrontation in the Court: Weakening the Institutional Independence

The Supreme Court of India which was crippled in its existence systematically by Gandhi constitutional Towers.

The most daring manipulation of the constitution to be engaged in by Gandhi was her very calculated compromise of the independence of the judiciary. Indian Constitution had accorded the judiciary status as a co equal organ of the state, and the Supreme Court was the last resort in any constitutional wrangles. Yet, judicial independence was not regarded by Gandhi as a protection of democracy but as a barrier towards her political ideologies.

The showdown arose because the Supreme Court started overturning some of the policies that Gandhi used to be known by such as her bank nationalization policy. Gandhi instead of accepting these legal ruling as an aspect of democratic right, opened a direct attack on the independence of the judiciary. She held a kind of weapon, that is Constitution itself, referring to the article of Constitution dealing with the judicial appointment and transfers.

Gandhi started by introducing tampering of the appointment of judges to make sure that they are appointed to be servants to her political interests. Constitutional requirement of consulting the Chief Justice was also interpreted in a creative way and Gandhi argued that consultation did not imply consent. This interpretation enabled her to adequately keep the judicial appointments at bay and continue with a camouflage in constitutional supposition.

The appointment of judges was another constitutional manipulation instrument. Gandhi utilized the section of judicial transfer which enabled her to punish judges who made adverse decisions against her government. Injurious decisions by High Court judges could only mean that these judges were either ousted to other undesirable postings and this terrified the independence of justices. The silence of the Constitution on the intended proceeding to carry out judicial transfer gave Gandhi the latitude which she required to introduce this policy of judicial intimidation.

Supersession Scandal: Killing Constitutional Conventions

Well-known Justice A.N. Ray, one of three judges overtaken, in controversial bid, in 1973 to become Chief Justice

Supersession of senior judges in the Supreme Court in 1973 was the the most explicit instance of gerrymandering with the constitution by Gandhi. Constitutional convention would have made the elder most judge, Justice J.M. Shelat the successor of Chief Justice S.M. Sikri on his retirement. But Gandhi had otherwise plans.

The fourth in line to the position, Justice A.N. Ray, had always ruled in favor of Gandhi government in crucial constitutional cases. Gandhi chose to outrule three more senior judges and install Ray as Chief Justice, and the action caused tremor across the legal fraternity and revealed her extreme attitude to annihilate constitutional norms to satisfy political ambition.

This action had a constitutional cover which though thin was technically legal. The President was delegated the authority in the Constitution to appoint the Chief Justice and the convention bound that seniority would be the major determinant factor but it was not a stipulated provision in the wordings of the Constitution. Gandhi used this ambiguity in order to have her way politically even as she kept up the semblance of some compliances to the constitution.

The three superseded judges resigned in protest, but the damage was done. Gandhi had successfully demonstrated that constitutional conventions, no matter how well-established, could be discarded when they conflicted with her political interests. The independence of the judiciary, one of the cornerstones of Indian democracy, had been effectively compromised through constitutional manipulation rather than constitutional amendment.

The Constitutional Amendment Weapon

Pages from the Indian Constitution showing the numerous amendments passed during Gandhi’s tenure to consolidate power

Gandhi’s most systematic assault on democratic institutions came through her use of the constitutional amendment process. The Indian Constitution had been designed to be flexible, allowing for amendments through a defined process that required significant parliamentary majorities. Gandhi recognized that this flexibility could be weaponized to consolidate power and eliminate constitutional constraints on her authority.

Between 1969 and 1975, Gandhi’s government passed a series of constitutional amendments that fundamentally altered the balance of power in Indian democracy. The 24th Amendment removed the President’s discretionary power to refuse assent to constitutional amendments, ensuring that Gandhi’s parliamentary majority could be used to reshape the Constitution without any institutional checks.

The 25th Amendment went further, removing the right to property from the list of fundamental rights and inserting a new article that prevented judicial review of laws related to the acquisition of property. This amendment was specifically designed to prevent the Supreme Court from striking down Gandhi’s nationalization policies, demonstrating how constitutional amendments could be used to retroactively legitimize questionable government actions.

Perhaps most ominously, the 26th Amendment abolished the privy purses and privileges of former rulers, effectively completing the process of eliminating potential sources of opposition to Gandhi’s government. While this move had popular support, it established the principle that constitutional amendments could be used to target specific groups or individuals,

a precedent that would prove dangerous in the years to come.

The Kesavananda Bharati Case: A Constitutional Inflection Point

Legal documents from the landmark Kesavananda Bharati case that established the “basic structure” doctrine

The Supreme Court’s decision in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala in 1973 represented a crucial moment in Gandhi’s constitutional manipulation strategy. The case arose from the government’s attempt to acquire land for agricultural reform, but it evolved into a fundamental challenge to the scope of parliamentary power to amend the Constitution.

Gandhi’s government argued that Parliament had unlimited power to amend the Constitution, including the power to alter or eliminate fundamental rights. This position would have given her government the ability to reshape the Constitution at will, effectively eliminating any constitutional constraints on her authority.

The Supreme Court’s decision, delivered by a narrow 7-6 majority, established the doctrine of the “basic structure” of the Constitution. This doctrine held that while Parliament could amend the Constitution, it could not alter its basic structure or essential features. The decision was a crucial victory for constitutional democracy, but it also marked the beginning of an even more intense conflict between Gandhi and the judiciary.

Gandhi’s response to the Kesavananda Bharati decision revealed the extent of her constitutional manipulation. Rather than accepting the Court’s interpretation of constitutional limits, she began planning ways to circumvent the basic structure doctrine. This planning would culminate in the Emergency of 1975, when constitutional democracy in India would be suspended entirely.

The Road to Emergency: Constitutional Preparations

The events leading up to the Emergency of 1975 demonstrate how Gandhi systematically prepared to suspend constitutional democracy using the Constitution’s own provisions. The maintenance of internal security act, the Defense of India Act, and various other pieces of legislation were crafted to provide legal cover for the suspension of civil liberties and democratic institutions.

Gandhi’s constitutional strategy was based on a careful reading of Article 352, which provided for the declaration of a national emergency in cases of external aggression or internal disturbance. The framers of the Constitution had intended this provision to be used in extreme circumstances, such as war or armed rebellion. However, Gandhi recognized that the vague language of “internal disturbance” could be interpreted broadly enough to justify emergency powers in response to political opposition.

The constitutional preparations for the Emergency were meticulous and revealing. Gandhi’s government began drafting legislation that would provide retrospective legal cover for actions taken during the Emergency. The 38th Amendment, passed during the Emergency, made the declaration of emergency non-justiciable, preventing the courts from reviewing the decision. The 39th Amendment placed the election of the President, Vice President, and Prime Minister beyond the reach of ordinary courts, ensuring that Gandhi’s own position could not be challenged through judicial review.

The Emergency: Constitutional Democracy Suspended

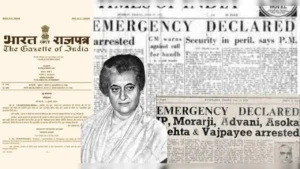

Front page of newspapers announcing the declaration of Emergency on June 25, 1975

When Gandhi declared the Emergency on June 25, 1975, she achieved the ultimate constitutional manipulation. Using the President’s power under Article 352, she suspended the fundamental rights of Indian citizens and assumed virtually unlimited power. The irony was not lost on observers: Indian democracy had been suspended using the very constitutional provisions designed to protect it.

The Emergency represented the culmination of Gandhi’s constitutional strategy. For nearly a decade, she had systematically weakened democratic institutions, manipulated constitutional provisions, and undermined the rule of law. The Emergency was not a sudden departure from democratic norms but the logical conclusion of a long process of constitutional subversion.

During the Emergency, Gandhi’s government passed a series of constitutional amendments that would have permanently altered the nature of Indian democracy. The 42nd Amendment, passed in 1976, has been called the “mini-constitution” because of its sweeping changes to the constitutional framework. The amendment severely limited judicial review, extended the term of Parliament and state legislatures, and gave the central government unprecedented power over the states.

The 42nd Amendment of 1976, known as the “mini-constitution,” which drastically altered the balance of power in Indian democracy

The 42nd Amendment also attempted to place the declaration of emergency beyond judicial review, ensuring that future leaders could use the Emergency provisions without fear of constitutional challenge. This amendment represented Gandhi’s attempt to constitutionalize authoritarianism, using the amendment process to legitimize the suspension of democratic norms.

The Aftermath: Constitutional Lessons and Legacy

Election results from 1977 showing Gandhi’s defeat, marking the end of the Emergency period

The end of the Emergency in 1977 marked the beginning of a process of constitutional restoration, but the damage to Indian democracy was profound and lasting. The Janata government that succeeded Gandhi attempted to undo some of the constitutional changes made during the Emergency, but the precedents established during this period continued to influence Indian politics for decades.

The 44th Amendment, passed in 1978, attempted to restore some of the constitutional safeguards that had been weakened during the Emergency. The amendment made it more difficult to declare an emergency, required written advice from the Cabinet for such declarations, and restored some of the judicial review powers that had been eliminated. However, the amendment could not undo the fundamental lesson of the Emergency: that constitutional democracy in India was fragile and could be subverted by a determined leader willing to manipulate constitutional provisions.

The Enduring Impact: Constitutional Vulnerability Exposed

Gandhi’s constitutional manipulation during the 1970s exposed fundamental vulnerabilities in the Indian constitutional system that persist to this day. Her systematic approach to undermining democratic institutions while maintaining the facade of constitutional compliance created a playbook that future leaders could follow.

The concentration of power in the Prime Minister’s office, the weakening of institutional independence, and the use of constitutional amendments to achieve political objectives all became normalized during Gandhi’s tenure. While subsequent governments have not resorted to the extreme measures of the Emergency, the constitutional precedents established during this period continue to influence Indian politics.

The Gandhi era also demonstrated the crucial importance of constitutional conventions and norms in maintaining democratic governance. The Indian Constitution, like most democratic constitutions, relies heavily on the good faith compliance of political leaders with unwritten norms and conventions. Gandhi’s willingness to disregard these conventions showed how quickly democratic institutions could be undermined when leaders prioritized political survival over constitutional propriety.

Lessons for Constitutional Democracy

The story of Indira Gandhi’s constitutional manipulation offers several crucial lessons for constitutional democracy in India and beyond. First, it demonstrates that constitutional provisions designed to protect democracy can be weaponized to undermine it when leaders are willing to prioritize power over principle. The flexibility that makes constitutions adaptable to changing circumstances can also make them vulnerable to manipulation by authoritarian leaders.

Second, the Gandhi era shows the importance of institutional independence in maintaining democratic governance. The systematic undermining of judicial independence, the manipulation of the appointment process, and the use of constitutional amendments to achieve political objectives all contributed to the erosion of democratic norms. Strong, independent institutions are essential for preventing the concentration of power that makes constitutional manipulation possible.

Third, the period highlights the crucial role of constitutional conventions and norms in democratic governance. While these unwritten rules may seem less important than formal constitutional provisions, they often serve as the first line of defense against authoritarian manipulation. When leaders begin disregarding constitutional conventions, it is often a sign that more serious constitutional violations may follow.

The Constitutional Paradox

The Indian Constitution – the very document designed to protect democracy became the instrument of its near-destruction under Gandhi

The story of how Indira Gandhi used the Constitution to subvert democracy represents one of the great paradoxes of modern Indian history. The very document that was supposed to protect Indian democracy became the instrument of its near-destruction. Gandhi’s systematic manipulation of constitutional provisions, her undermining of institutional independence, and her willingness to suspend democratic norms revealed the fragility of constitutional democracy when faced with a determined authoritarian leader.

The legacy of this period continues to shape Indian politics today. The constitutional amendments passed during the Emergency, the precedents established for executive power, and the normalization of constitutional manipulation all remain part of the Indian political landscape. While Indian democracy survived the Emergency and has continued to function for nearly five decades since then, the lessons of the Gandhi era serve as a constant reminder of the vigilance required to maintain constitutional democracy.

The ultimate irony of Gandhi’s constitutional manipulation is that it was her respect for constitutional forms that made her subversion so effective. By maintaining the facade of constitutional compliance while systematically undermining democratic institutions, she demonstrated that the greatest threats to constitutional democracy often come not from those who openly reject constitutional norms, but from those who manipulate them for authoritarian ends.

As India continues to grapple with questions of executive power, institutional independence, and constitutional interpretation, the Gandhi era serves as both a cautionary tale and a source of valuable lessons. The woman who once proclaimed herself the embodiment of India ultimately became the embodiment of the threats that constitutional democracy faces when leaders prioritize power over principle and political survival over democratic norms.

The constitutional manipulation of the Gandhi era represents a dark chapter in Indian democratic history, but it also demonstrates the resilience of democratic institutions and the importance of constitutional safeguards. The fact that Indian democracy survived this period and emerged stronger suggests that while constitutional democracy may be fragile, it is not easily destroyed. However, the lessons of this period must not be forgotten, as the techniques of constitutional manipulation perfected during the Gandhi era remain available to future leaders who may be tempted to follow a similar path.

In the end, the story of Indira Gandhi’s constitutional manipulation serves as a reminder that democracy is not a destination but a continuous journey, requiring constant vigilance and commitment from both leaders and citizens. The Constitution may provide the framework for democratic governance, but it is the commitment to democratic norms and values that ultimately determines whether that framework will protect or undermine the democracy it was designed to serve.